Fiery Emblems of an Alchemist

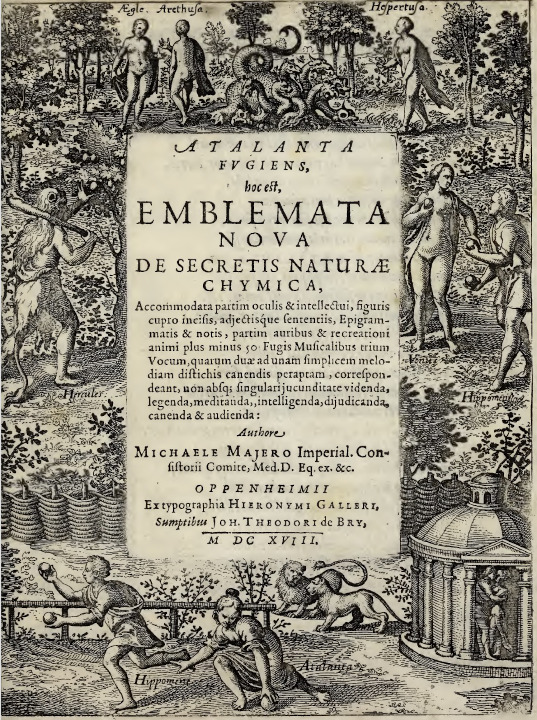

Books about alchemy from the late Renaissance sometimes include extraordinary images featuring fire. Though I plan to include a couple of these in my cultural history of fire, others wander too deeply into arcane philosophical backwaters to float in my main stream. Here are some delightfully strange images from Atalanta fugiens (The Flying Atalanta, or, Philosophical Emblems of the Secrets of Nature), a book of fifty discourses by Michael Maier (Michaelis Majeris) first published in Oppenheim (now in Rhineland-Palatinate) in 1617. An early example of “multimedia,” some of its images were collaged into an interactive multimedia work of my own published in 1995.

Though detractors later characterized alchemists as secretive mystics obsessed with turning other metals into gold, they pioneered many innovations in laboratory techniques, metallurgy, medicine, and chemical analysis, setting the stage for the Scientific Revolution. Some of the most important early scientists were alchemists, including Isaac Newton, astronomer Tycho Brahe, and Robert Boyle (the first modern chemist). Secretive they certainly tended to be however, and mystics, searching for systems of meaning hidden within even deeper systems of meaning. Their works revel in multiple layers of symbolism and dense discursive allusions.

Presented in “emblem books,” a popular genre of the period, emblemata could represent moral concepts, allegories, or persons. Each discourse in Atalanta fugiens contains an engraved emblem by Matthias Merian, epigrammatic verse set to music, and text explicating the rest. These discourses allegorize, through many enciphered layers of allusion, the long sequence of metallurgic and spiritual steps alchemists used in the attempt to create the philosopher’s stone, a panacea capable of restoring humankind to Edenic health and longevity.

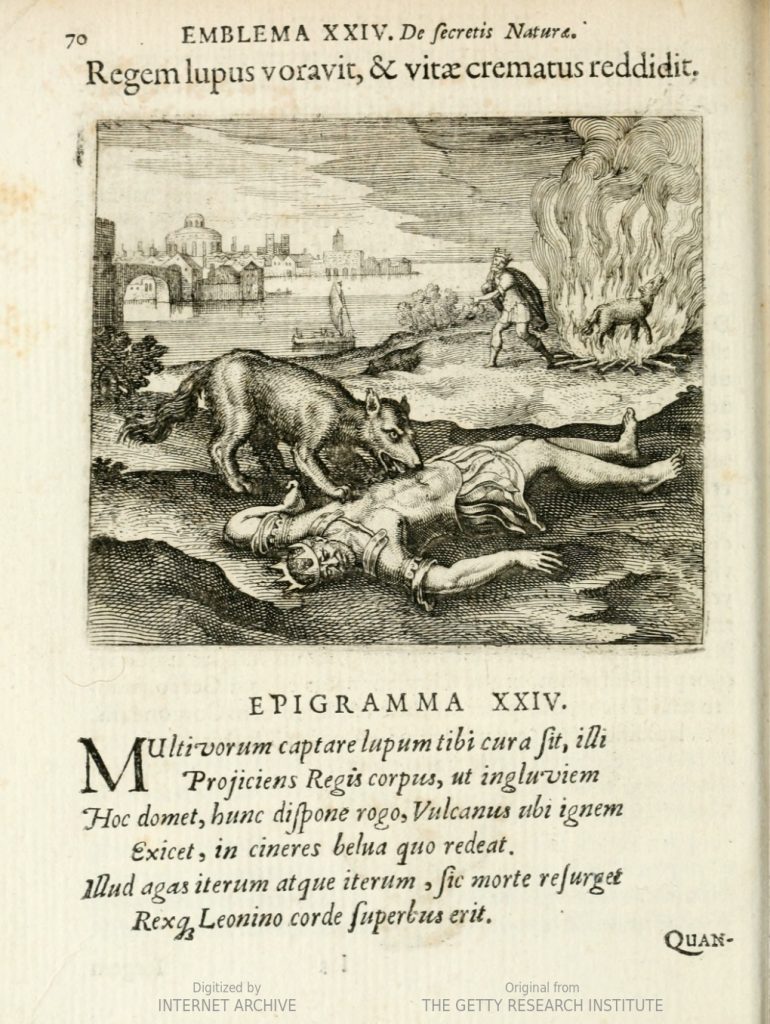

Emblem XXIV. A wolf devoured the king, and being burnt it restored him to life again.

The twenty-fourth discourse allegorizes the process of purifying gold (“the lion”) by firing a mineral containing gold and sulfur (“the king”) with a compound containing antimony (known as the “grey wolf” for its tendency to “devour” other metals into alloys). It can be difficult to make sense of Maier’s text. Like many emblem books, Atalanta presents its readers with intellectual puzzles, hiding (or extending) meaning within riddles and discursive stories. Unlike symbols, which embody ideas in ways designed to be widely understood, emblems hide their true significance in ways that challenge the sophistication of the viewer’s understanding.

After giving dubious accounts of the burial customs of various cultures (“The Hyrcanians nourished Doggs for no other Use but that they might cast their Dead Bodyes to be devoured by them”) Maier stretches the story out at great length, ostensibly telling stories of Indian kings, how the Wolf raised in cold regions works better because hungrier than those bred in Libya and Egypt—on and on. “From their King devoured by a wolf there will appear one that is Alive, Strong and Young, and the wolf must be burnt in his stead…” All of which makes little sense until you grasp the hidden metallurgic meaning of “wolf” and “king” and understand that the mysterious “one” ultimately produced is purified gold.

Emblem XXX: The Hermaphrodite, lying like a dead man in darknesse, wants Fire.

Here Maier recounts the many transformations heat and fire can effect, including stories of Trans men and women from Classical times. Pliny for example recounted two cases of women who, after getting married, grew beards and became men. Maier seems to believe that heat can trigger transition between genders. At times he can sound quite matter of fact and modern about such matters: “Nature being dubious whether she should generate a man or a woman expresses a woman outwardly, tho’ inwardly she intended a man.” Then however he asserts that “as heat and motion increase with Age the hidden parts break forth and become apparent.” He cites a famous Genoese surgeon who changed a “noble youth that was an Hermaphrodite…into a perfect man not uncapable of getting Children.”

Though these stories reveal surprisingly modern understanding of gender fluidity in real-world human beings, they are only surface analogs to Maier’s primary interest: a form of philosophical hermaphroditism that held great significance for alchemists. The action of fire can combine the female and the male, they believed. “The coldnesse and the moistnesse of the Moon” and “the heat and drynesse of the Sun” can together create a Rebis (from the Latin res bina, “double matter.”) This magnum opus (great work) of the alchemists produces a reconciliation of spirit and matter known as the “divine hermaphrodite.”

Emblem XXIX. As the Salamander lives in fire, so also the Stone.

A section of my chapter on “Creatures of Fire” traces the history of the belief that salamanders could live in fire. Even the scientific pioneer Leonardo da Vinci believed that the salamander “has no digestive organs, and gets no food but from the fire, in which it constantly renews its scaly skin.”

Amphibious salamanders find the damp interiors of hollow logs ideal places in which to hide—until some human rudely throws their cozy shelter onto a fire. The surprising sight of salamanders escaping from the midst of flames very likely gave rise to the belief that they actually live in fire.

Emblem XX: Nature teaches Nature how to subdue Fire.

After describing how birds teach their young to fly and other examples of learning from the animal kingdom, Maier draws analogies with the way certain substances “teach” others when combined in metallurgy. A special alchemist glaze called Eudica “will cure bodyes changed into Earth from any burning. For when bodyes do no longer retein their souls they are soon burnt.” After a long string of classical references and medical speculations, he recommends following this train of thought “as the most clear example of the Philosophickal Work.” Since for modern readers his examples will not be clear at all, Scottish expert Adam Maclean offers a year-long study course called How to read alchemical texts: An introductory study course for the perplexed.

Emblem X. Give Fire to fire, Mercury to Mercury, and you have enough.

Illustrator Mattias Merian has fun here showing a discomfited god Mercury letting his caduceus droop when introduced to another version of himself already sitting calmly by the alchemist’s hearth. In a chapter of my book entitled “What Is Fire?” I detail how the alchemists replaced the classical elements air, water, earth, and fire with a three-element primal triad consisting of the “philosophical” elements sulphur, mercury, and salt. These were not exactly the familiar substances known by those names, but rather idealized forms representing the fundamental principles combustibility, volatility, and fixity. The two gods being introduced to each other in this image may be the sort of mercury you can extract from cinnabar on the one hand and the philosophical principle of volatility on the other. Or maybe not… the text of this discourse runs particularly abstruse. For example:

Color was added in the 18th or 19th century to the first ten emblems of a 1618 copy of Atalanta fugiens. Science History Institute Museum and Library

“The internal Fire is Equivocally so cold because of its fiery qualities, virtue, & operation, but the External Fire is Univocally so. Therefore, External Fire & Mercury must be given to the internal Fire & Mercury, that so the intention of the Work may be completed… The Philosophical Infant must be nourished by Fire as with Milk, & the more plentiful that is, the more he grows.” Got that?

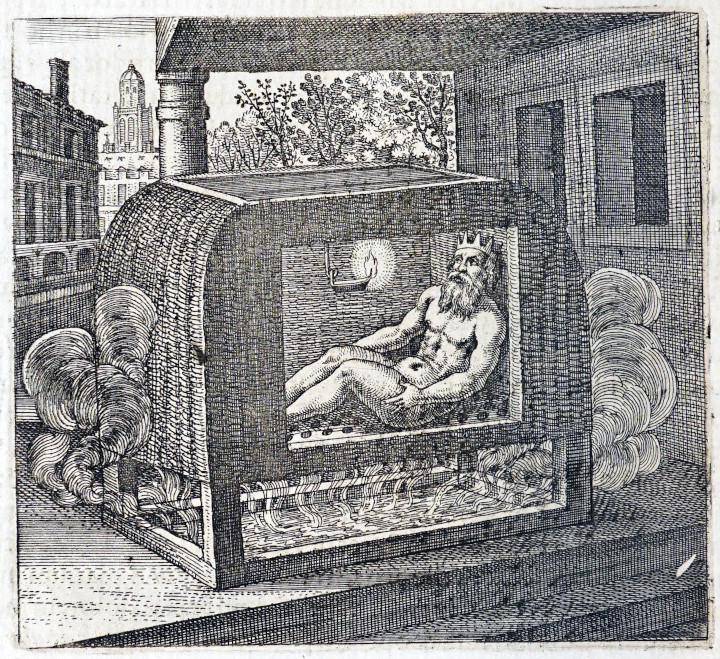

Emblem XXVIII The king bathes sitting in the water-bath [Laconicum], and he is freed from black bile by Pharut.

This emblem allegorizes a particular device in the alchemical laboratory apparatus: the vapor bath. The king represents matter held in a vessel above a source of steam so as to “sweat away” impurities. The text tells the story of how a physician named Pharut cured a certain King Deunech of melancholy by sweating out his “black bile” with steam.

Though not all the emblems in Atalanta fuguiens depict fire directly, fire is important throughout. Each of the seven metallurgic operations key to the alchemical process involves a specific type of flame and degree of heat. Through these “gates” or “keys” matter gets broken down into constituent elements, recombined, and purified.

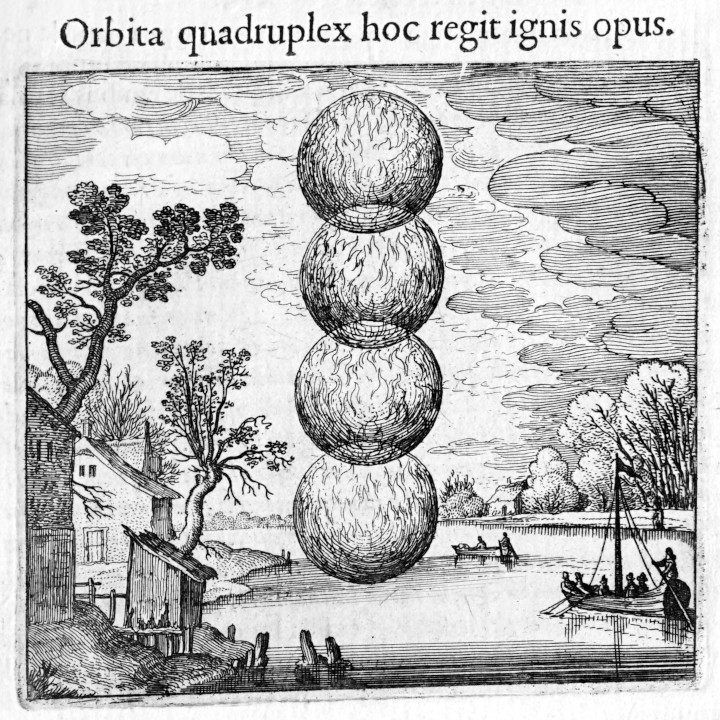

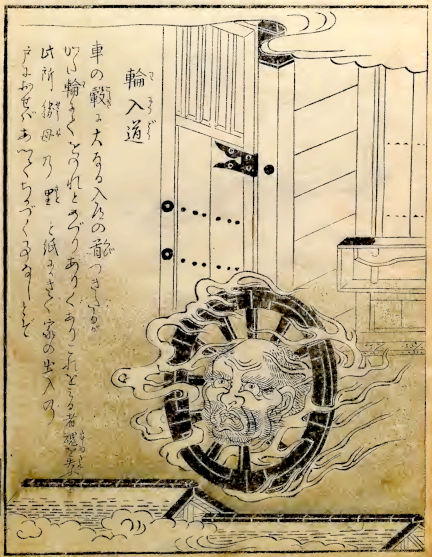

Emblem XVII: The fourfold wheel of fire reigns over this work.

The four interlocking orbs in Emblem XVII, each of which contains enclosed flames, allegorize the process of Sublimation. After heat vaporizes a solid substance, cooling these vapors produces a more concentrated substance. The epigram and text draw concepts from several sources including the Jewish mystical tradition of the Kabbala (the Four Worlds or spiritual realms that comprise Creation) and classical mythology. The fire in the lowest sphere, produced by the craftsman god Vulcan, sublimates material that passes through an airy sphere of Mercury, then the watery sphere of Luna, and finally congeals again in the uppermost sphere of Apollo, associated with earth, gold, and the alchemist’s ultimate goal, the philosopher’s stone.

In addition to the typical combination used in many emblem books of image, epigram, and explicatory text, each of the fifty discourses in Atalanta fugiens also sets the epigram to music. Polyphonic vocal compositions, which Maier called “fugues,” weave together three voices: “Atalanta fleeing,” a Greek huntress, famously fleet of foot; “Hippomenes following,” the suitor who challenged her to a race and only managed to beat her with divine help; and “the Delaying Apple,” the golden apples Aphrodite gave Hippomenes so as to distract Atalanta, enabling him to win the race. Like everything else in Atalanta fugiens the three voices have multiple additional meanings, such as representing the tria prima: mercury, sulphur, and salt.

According to scholar Donna Balik, this blending of different media makes Atalanta fugiens an early example of multimedia. She created a delightful online version that allows us to hear a recording of each musical fugue while contemplating its image and epigram.

Here the double-page layout of Emblem III, Go to the woman who washes sheets and do likewise,

displays the epigram in both Latin and German. Allegorizing Calcination, the first of seven steps or “keys” in the alchemical process of metallic transformation, this discourse instructs us, when cleansing philosophical matter of impurities, to follow the example of the washer-woman’s attention to the proper way to go about washing sheets.

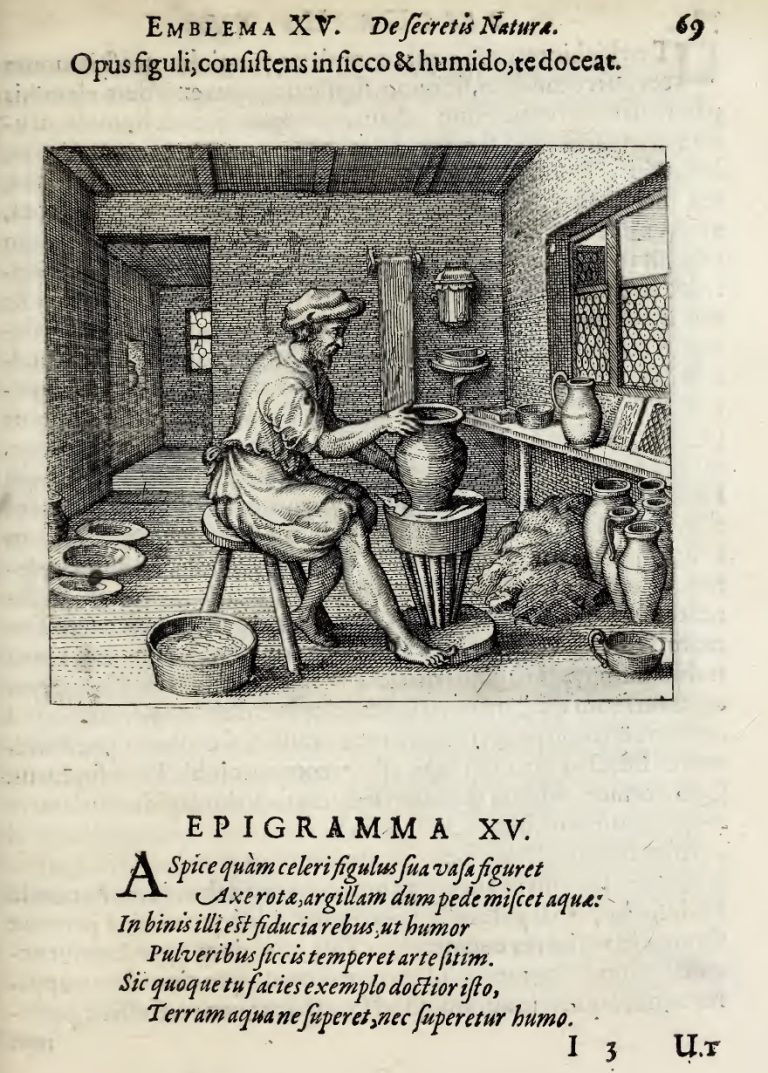

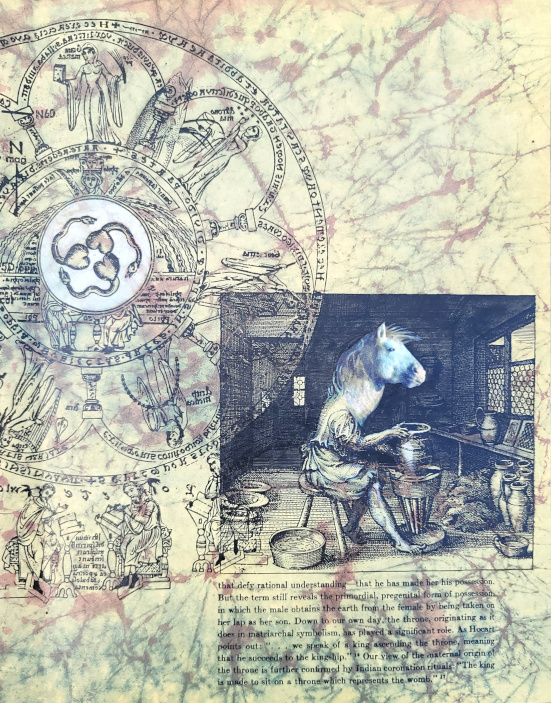

I was surprised and delighted to find familiar imagery in Atalanta fugiens. In the early 1990’s collage artist Tennessee Rice Dixon incorporated several emblems, which she found at the New York Public Library, into an artist book she called ScruTiny in the Great Round. These included Emblem XV, Let the work of the Potter, consisting in drynesse and moisture, instruct you.

Some years later I worked with Tennessee to turn ScruTiny into a multimedia CD-ROM using Macromedia Director, an application for creating interactive multimedia presentations. We scanned the eleven main pages of the book into digital files and added animations, music and sound effects by composer Charlie Morrow, and navigational devices, including replacing the computer cursor with small images (sprites) representing the sun, the moon, and a fish. Published in 1995 by Calliope Media, the interactive multimedia ScruTiny won several awards, including the Grand Prix d’Or at MILIA in Cannes.

So some of these images from a seventeenth-century book form of multimedia found their way to an twentieth-century artist book, then to a digital form of interactive multimedia. An alchemical transformation of sorts.

[An earlier blog post also features intriguing fire images that won’t make it into my book, as does my Instagram account.]

Sources

Bilak, Donna, “Chasing Atalanta: Maier, Steganography, and the Secrets of Nature” furnaceandfugue.org/essays/bilak

Bilak, Donna, “Atalanta fugiens (1618): Music-Image-Text”

atalantachf.omeka.net

Maclean, Adam, “Alchemical Texts: Atalanta fugiens”

alchemywebsite.com/atalanta

Maier, Michael, Atalanta fugiens, hoc est, Emblemata Nova de Secretis Naturae Chymica (Theodoris de Bry, 1618) Science History Institute Museum and Library

Nummedal, Tara and Donna Bilak, Furnace and Fugue: A Digital Edition of Michael Maier’s Atalanta fugiens (1618) with Scholarly Commentary (University of Virginia Press, 2020) furnaceandfugue.org

I am still fiddling with the main title of my book. Fire in the Mind? Fire in the Imagination? Imagining Fire? Everyone seems to like the subtitle. Opinions welcome! Add a comment below.

Fiery Emblems of an Alchemist Read More »

I spent a productive few days at the San Francisco Writers Conference, attending for free after winning the Grand Prize in their 2022 writing contest. Highlights were the many informative “breakout sessions” with agents, acquiring editors, independent editors, writing coaches, and book publicists. Aside from a few useful contacts, the conference gave me good ideas for honing my book proposal, which I continue to carefully craft.

I spent a productive few days at the San Francisco Writers Conference, attending for free after winning the Grand Prize in their 2022 writing contest. Highlights were the many informative “breakout sessions” with agents, acquiring editors, independent editors, writing coaches, and book publicists. Aside from a few useful contacts, the conference gave me good ideas for honing my book proposal, which I continue to carefully craft. I found I could get a surprising number of questions usefully answered in eight minutes. I had a good session with a guy who would be an excellent choice for an agent, once I decide to send out pitches. He thought I had a good subject and had made a good choice in a “comp” (a successful book with similarities to mine. At the top of my list is Salt by Mark Kurlansky.)

I found I could get a surprising number of questions usefully answered in eight minutes. I had a good session with a guy who would be an excellent choice for an agent, once I decide to send out pitches. He thought I had a good subject and had made a good choice in a “comp” (a successful book with similarities to mine. At the top of my list is Salt by Mark Kurlansky.) Many careers ago I had experience on the other end of the permissions game when I briefly worked for a well-known literary agency in Manhattan. Among my early responsibilities were lugging home fat manuscripts of bad novels from the slush pile and handling permissions. Requests would come in for permission to use a story by Ken Kesey, say, or Erica Jong, and I would write back saying how much it would cost. Here was a chance to shine! $100 for a chapter in an anthology? No! I’d ask for $200. I doubt I impressed anyone by driving hard bargains as the Permissions Department, but now, with some trepidation, I imagine someone like my 22-year-old self reviewing my requests.

Many careers ago I had experience on the other end of the permissions game when I briefly worked for a well-known literary agency in Manhattan. Among my early responsibilities were lugging home fat manuscripts of bad novels from the slush pile and handling permissions. Requests would come in for permission to use a story by Ken Kesey, say, or Erica Jong, and I would write back saying how much it would cost. Here was a chance to shine! $100 for a chapter in an anthology? No! I’d ask for $200. I doubt I impressed anyone by driving hard bargains as the Permissions Department, but now, with some trepidation, I imagine someone like my 22-year-old self reviewing my requests.